Article from 1988 Saturday Evening Post Society about Paul Anderson.

He was there when the country needed him–a man possessed not only of physical greatness, but the heroic qualities of kindness and good common sense.

In 1955, Americans needed a hero. Toe-to-toe with the Russians in the Cold War, tightly locked in a propaganda battle pitting Our Way against Their Way, we’d even begun to doubt ourselves.

Low fitness scores by elementary-school children and a high number of draft rejections during the Korean War pointed to our declining physical abilities. The clincher had been the Russians’ phenomenal showing in the 1952 Olympics–the first Games the Soviets had attended.

Clearly, we needed a man of action, of physical power–a strong man who also possessed other heroic qualities: kindness, gentleness, and good common sense.

When he appeared, it was in the best heroic tradition: he arrived on the scene virtually overnight.

Out of Nowhere

In June 1955, Paul Anderson went to Moscow as the least known of six American weightlifters who were to meet the Russians in the first athletic competition held solely between the two countries since World War II. The Russians were visibly disappointed when he stepped off the plane as a replacement for the injured American champion heavyweight.

“How will you identify yourself with your team?” he was asked.

“When they load the barbell, they’ll know who I am,” he said.

In the first of three required lifts–the two-hand press–the Russian lifted 330.5 pounds, his personal best. The crowd cheered deliriously, and many assumed the short, fat American would not even try to match that figure. Paul called for 402.4 pounds. The crowd gasped; the weight was more than 20 pounds over the world record. Was this a joke?

The announcer dryly informed the crowd that officials were being meticulous in loading the bar because “we very rarely have such weights lifted.” Fans snickered.

When Paul lifted the 402.4 pounds, there was dead silence for ten seconds. “I felt like the man at the end of the newscast who says good night and the camera stays on him,” Paul recalls. Then the crowd went wild. It continued cheering uproariously when he set another record for clean and jerk. “He’s a wonder of nature!” many screamed.

Overnight, Paul Anderson, the squat, round replacement, had become the “Strongest Man in the World.”

Of course, “overnight success” is never really achieved that way. It’s the result of years of dedication, hard work, and faith. Paul had known for a long time that he could outlift any other human being. He’d also nearly despaired of ever getting the chance to prove it.

Building a Mountain

Paul Anderson was born on October 17, 1932, at Toccoa, Georgia, a small rural town in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. “In high school, I wasn’t supposed to be any stronger than anyone else. I’d had all these kidney diseases and rheumatic fever before I was six,” he recalls.

Nonetheless, he earned a football scholarship to Furman University. He stayed for only a little more than a semester, but it was at Furman that he began lifting weights. He quickly discovered he had a natural ability. “It was very encouraging to me that some of the people had been lifting since they were little tykes and I could lift far more than they could,” he says.

Back in Toccoa, he put himself on a specially designed natural diet that greatly expanded his strength and his girth. His homemade “gym” consisted of weights of concrete blocks and bars from truck axles–primitive but effective.

Part of his training regimen was to work with heavier weights than he’d have to lift in competitions. “My idea was that if you were going to be a weightlifter, be strong first. Then you can work on form,” he says. He progressed quickly.

“I could have won the world championship at any time from 1952 on, but I always had injuries,” he continues. “The first competition I won was the North American championship in Montreal in 1953. Then I broke my wrist before I could go with the team to Europe. Later, I was in a car wreck and broke some ribs and hurt my hips. Another time I tore up my knee. I really think it was the good Lord putting me in the right place at the right time.”

After the Moscow meet in which he established himself, Paul took the world heavyweight championship at Munich in October with a record total for three lifts. He was virtually conceded the Olympic title in 1956 at Melbourne–if, for once, he could stay healthy. It was a big “if.”

Melbourne, 1956

When Paul Anderson represented the United States at the Melbourne Olympics, the weight he had to contend with was even greater than his world record. He was carrying the nation’s hopes on his broad back.

Should an American of awesome international repute–namely, Paul Anderson–be vanquished in an event that he seemed certain to win, the embarrassment would be national.

Under his photo in the Melbourne newspaper was a caption suggesting that all he needed to do was drop by the arena to pick up his gold medal. The only way the “Strongest Man in the World” could lose was if he broke a bone or was sick.

And sick is precisely what Paul Anderson was in Melbourne. He was suffering from an inner-ear infection that affected his balance. He’d run a fever for two weeks and dropped 30 pounds in body weight. In his own words, he was “feeling punk.” Three days before the event, the doctors told him they would not let him lift.

“Lift?” he said with a gasp. “I can’t even walk!”

Nevertheless, Paul begged them to put off their decision until the last minute. When they agreed, he went back to his room and started gobbling aspirin “like goober peas.” On the day of the competition, the fever came down, but he still felt as bad.

“How do you feel?” the doctors asked him.

He would not lift until midnight, he remembers: “I went to a movie. Later, when I went to the arena, the aspirin had worn off and my fever shot back up to about 104. I felt terrible, but I suited up and did some warmups.”

His competition did not come from Russia. The Soviets hadn’t bothered to send a heavyweight, so certain were they that the “Wonder of Nature” would win easily. But every other heavyweight who had expected to scuffle for silver now saw a chance for gold.

“It’s ironic,” Paul says. “Just two weeks before, I didn’t have any competition in the world. But that one night, everyone was my competition. I feel it was God showing me that I need Him.”

It finally came down to Paul and Argentina’s 316-pound Humberto Selvetti, having perhaps the night of his life. On the third of the South American’s required three lifts, he brought his total to 1,102 pounds.

Paul had totaled far more than that before, but not when he was so ill he could barely stand. The fever had dropped his weight to an official 304. Under weightlifting rules, as the lighter contestant, he had only to tie Selvetti’s weight total to win. But he was trailing so badly after two lifts that to tie required an Olympic record 413.5-pound lift in the clean and jerk.

Quietly, Paul asked for 413.5. It was three in the morning. He was reeling, sweating, near collapse. Twice he tried to lift the record weight and failed.

Then, like a modern Samson, Paul asked God for the little extra his straining muscles needed. “I wasn’t making a bargain,” he insists. “I needed help.”

Wire services described how Paul’s 52 1/2″ chest expanded to near bursting as he made his final lift, and how he finally held the weight high in Olympic victory.

“I would have liked to have gone out with fire and thunder,” Paul admits. “But as I look back, getting sick was one of the best things that ever happened to me. It gave me a type of humbleness.

“All my setbacks have been physical,” Paul says today. “And all my victories have been physical.” The kidney problems of his youth returned; eventually he had a transplant. In 1985, he suffered a burst colon. “The doctors gave me a 20 percent chance of living. The Lord gave me 100 percent,” he says. “In October of last year, I had two new hip joints put in, both at one time. I’m coming back now. I just turned it all over to the Lord.”

Paul’s deep faith, shared by his wife, Glenda, is at the core of what many would call his most enduring achievement: the Paul Anderson Youth Home in Vidalia, Georgia.

Since 1961, the home–along with two others later established in Texas–has provided an alternative to juvenile penal institutions for troubled and homeless boys. To date, more than a thousand teenagers, mostly from broken homes, have gained a new measure of self-worth through the Andersons’ potent blend of hard work, love, and faith.

Until his latest round of physical ills, Paul was on a nearly constant speaking tour to raise money for his youth homes. Averaging 500 speeches a year, he mixed humor (“I was a 97-pound weakling–when I was four years old!”), a hard sell for God (“I couldn’t get through a day without Him”), and such strength stunts as driving a nail with his bare fist.

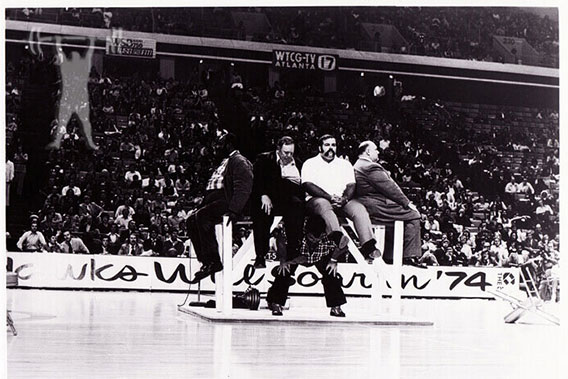

His show-stopper, raising on his back a table loaded with eight men, was really a “light” weight for Paul. The Guinness Book of World Records (1985 edition) lists his feat of lifting 6,270 pounds in a back lift as “the greatest weight ever raised by a human being.”

In his speeches around the country, Paul has described many times how on this third and last try at Melbourne he got the record weight to his chest and suddenly knew that he could lift it no higher. Alone. He tells his audience how in that brief split second, he made his lifetime affirmation to God.

Then he explains that he values the gold medal he brought back from Melbourne, and he’s proud of his many other honors: “But the greatest thing in the world is my faith.”

Stay Updated

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and weekly devotional